A quiet doorway at Babcock & Wilcox plant, Renfrew once opened onto a moment that would change the world. On 21 July 1955, Professor Ian Donald stepped through it — and into history.

That very door now being commemorated with a special plaque. Hosted by novosound, in partnership with Renfrewshire Council, Altrad, and Westway, the plaque honours Scotland’s remarkable legacy in medical innovation, and the future being shaped by novosound’s wearable ultrasound technology.

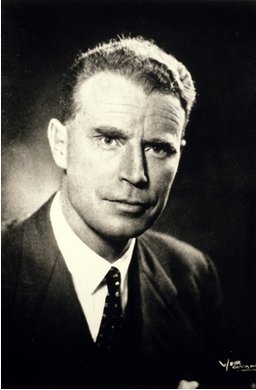

Born in Cornwall on 27 December 1910 to Dr John Donald and Helen (née Barrow Wilson), Ian came from a long line of doctors. His father, a general practitioner, traced his roots to a Paisley medical family, and his grandfather had also been a GP. His mother, a concert pianist, brought music and culture into the home. Ian was the eldest of four siblings — Margaret, Malcolm, and Alison Munro, the latter of whom would go on to become a pioneering headmistress.

Donald’s early education began at Warriston School in Moffat, followed by Fettes College in Edinburgh. But the family’s life took a dramatic turn when his father fell ill, prompting a move to South Africa. There, at Diocesan College in Rondebosch, Ian developed a love of the classics, languages, philosophy, and music.

Tragedy struck in 1927 when diphtheria swept through the family. His mother died of a heart attack, and just three months later, his father also passed away. Donald, only 17, was left orphaned along with his siblings. Their housekeeper, Maud Grant, was entrusted with their care through a family trust.

That same year, Ian graduated with first-class honours in arts and music from the University of Cape Town — a remarkable achievement under such difficult circumstances. In 1930, the family returned to London, where Donald pursued medicine at St Thomas’s Hospital Medical School, University of London. By 1937, he had qualified with a Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery, becoming the third generation in the Donald family to wear the white coat.

He also found love: marrying Alix Mathilde de Chazal Richards, a farmer’s daughter from the Orange Free State in South Africa.

His career took a pivotal turn during World War II, when he served as a medical officer in the Royal Air Force. There, he became fascinated by radar and sonar technology — tools being used to detect submarines and aircraft. Donald began to imagine how similar waves might be used not to search the seas, but to see into the human body.

After the war, Donald’s curiosity blossomed into innovation. At St Thomas’ Hospital in 1952, he created a respirator for newborns with breathing difficulties. Later, at Hammersmith Hospital, he developed the Trip Spirometer and the Puffer, both pioneering devices to help newborns breathe more effectively.

In 1954, he was appointed Regius Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the University of Glasgow. There, a chance encounter would again change the course of medical history. At the Western Infirmary, he met Tom Brown, an engineer from Kelvin Hughes. Together, they built the world’s first obstetric ultrasound machine: the Diasonograph, unveiled in 1963.

Thanks to Donald’s vision, it became possible to see inside the womb, allowing doctors to detect abnormalities, monitor development, and reassure expectant parents. The Diasonograph helped lay the foundation for modern prenatal care.

He also campaigned successfully for the construction of the Queen Mother’s Maternity Hospital, located next to the Royal Hospital for Children in Glasgow — a lasting symbol of his dedication to maternal and neonatal care.

Donald retired in 1976, though he continued contributing to innovation through a consultancy with Nuclear Enterprises in Edinburgh until 1981. He spent his final years in the Essex village of Paglesham, where he passed away on 19 June 1987. He was survived by his wife, four daughters, and thirteen grandchildren, and is buried in the churchyard at St Peter’s Church.

From a wartime fascination with radar to the life-saving clarity of prenatal scans, Ian Donald’s story is a testament to resilience, imagination, and the enduring power of asking, “What if?”